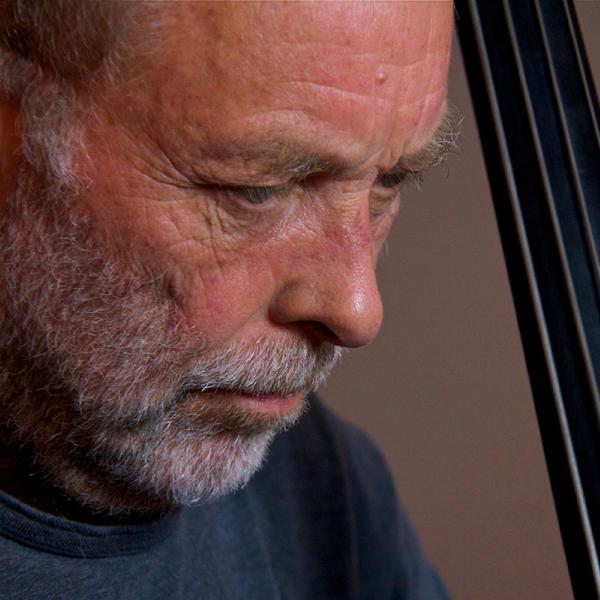

Scott Yoo

Music Credits:

Geoff Nuttal and the St. Lawrence Quartet perform Haydn's classic Emperor Quartet and

The Dover Quartet and Brook Speltz perform Franz Schubert’s String Quartet in C. Both courtesy of Now Hear This.

“NY” composed and performed by Kosta T from the cd Soul Sand, used courtesy of the Free Music Archive.

Scott Yoo: For me, one of the really gratifying things about making this show is that I’m constantly learning myself. I did not know the extent to which Haydn really lived in a cultural melting pot, sort of on the border of what we call Austria now and Hungary with sort of Viennese influence and gypsy influence. It’s really fascinating, and it’s fun to actually get to travel to where these composers actually lived, go to where they died, go to where they lived, where they were born. It’s really a privilege to get to be a part of something like that.

Jo Reed: Scott Yoo is a renowned violinist, the conductor and artistic director of the Mexico City Philharmonic, the musical director of festival Mosaic and the host of Now Hear This, a four-part documentary miniseries now in its second season presented by Great Performances. Now Hear This merges music, storytelling, travel, and culture as it explores the music of great composers in western culture. Season 1 began with the Baroque period: digging into the music of Vivaldi, Scarlatti, Bach and Handel. Season two moves into the classical period with explorations into Haydn, Schubert, Mozart, and Beethoven. It is a dream of a series---especially appreciated during the pandemic as both travel and the performing arts are mostly out of reach. Now Hear This travels around the world to do a deep dive into the geographic, social and cultural landscapes that shaped the composers who created this glorious music. As you can hear, I’m a fan, and it was with great pleasure that I spoke with Scott Yoo on a warm October afternoon after an evening of binge-watching Now Hear This.

Scott, first of all, thank you so much for joining me. I really appreciate it. I spent last night watching three episodes of “Now Hear This,” and I had a fabulous time so thank you

Scott Yoo: Wow. That’s such an honor. Thank you for saying that.

Jo Reed: It’s true. Thank you.

Jo Reed: Could you describe the show for people who might not have encountered it?

Scott Yoo: Sure. It’s Anthony Bourdain, but we’ve substituted music for food.

Jo Reed: That’s a great description. How do you create a show that actually allows that to happen? What’s the format?

Scott Yoo: Well, it’s not I who creates the show. It’s my good friend and partner in crime, Harry Lynch.

Harry is not just the writer, but he’s also the producer and the director for the episodes. And what he’s trying to do is not just have a collection of scenes, but actually tell a story, and that’s, I think, one of the reasons why the show has been quite successful. What I love about the show is that it not only incorporates what I love, music, but it also incorporates travel, which is something I love and maybe a little mystery, maybe a little surprise somewhere. A lot of the times when we’re shooting these episodes, we’re discovering things along the way too. And so sometimes we will be surprised, “Oh, I didn’t know that,” and then the story will go in a completely different angle, and then we’ll have to just sort of improvise.

Jo Reed: There was a lovely moment in the Vivaldi show in which you found yourself looking at some of his original manuscripts of music that he wrote, and it clearly moved you. Can you tell me about that moment for you?

Scott Yoo: Oh, that was so cool, Jo. I think that for a young kid in Little League, to get to step onto the field of Fenway Park or Yankee Stadium or Wrigley Field would be like the thrill of a lifetime. For me, I listened to what I was reading as a child. That was kind of my childhood soundtrack. To actually see the very paper that Vivaldi wrote on-- he touched that paper. He was making little dots on that paper that I was reading. It was straight from the source. And for me, that really was a chilling moment. I never thought that I would actually get to touch that personally. I had gloves on, of course, but I don’t know. It’s one of those moments you’ll never forget.

Jo Reed: Yeah. It’s so interesting, right? It’s like history just collapses on itself in some way.

Scott Yoo: You know, Jo, what I love about music is that it lasts forever. It’s not like a dinner that, you know, a three star Michelin restaurant will make, and it’s probably good for five minutes or maybe even two minutes and then it’s not good anymore. You have to eat it right away and consume it. Music lasts forever and yet, it happens in the present moment, meaning for it to actually be art, somebody has to play it. Of course, Vivaldi’s “L’Amoroso Concerto,” which I was sight reading in Turin, of course, that manuscript is the art. But, actually, the art really doesn’t happen until you’re actually playing it, and that-- I don’t know. For me, that’s very special.

Jo Reed: Well, you know, you make it a point for each show to have a different, I don’t know, entry point into the composer. And for Haydn, for example, the focus is his string quartets, and you call him “The King of Strings.” And the man wrote, what, 100- some odd symphonies. And I was really so taken aback that you approached through his chamber music rather than his symphonic work. Tell me your thinking here.

Scott Yoo: You know, Jo, I think that’s a really incredible perceptive question. We talk a lot about giving the public as many different points of entry into the art form as possible. This show started because-- I run a festival in California called Festival Mosaic, and we have a series called “The Notable Encounter.” And that series is kind of a museum docent’s guide, but not to art, not to visual art, but to classical music. And it was inspired by what they do, say, at the Moma. And what fascinated me being a member of the Moma for many years was how many different points of entry they gave to an art form-- what fascinated me about the Moma was how many different points of entry they gave to a particular piece of art, say like a Kandinsky.

Jo Reed: And just to clarify, you’re talking about the Museum of Modern Art in New York City which has an app you can download on to your phone and it will tell you about the art you’re seeing as you go through the building.

Scott Yoo: Yes, exactly. If you type in 37, it speaks to you as if you’re an adult, and it tells you about Kandinsky’s life and what he was feeling and what he was experiencing when he created the piece. If you type in 38, it’s talking to you as if you’re a 14-year-old interested in rap music, and it says, “Yo, yo, kick it. I’m here to talk to you about Kandinsky. He’s my main man.” If you type in 39, it talks to you as if you’re blind, and it describes what the canvas feels like and how large it is, and it’s fascinating. They’ve done a brilliant job of giving as many points of entry into the art form as possible. And so I think when Harry writes these episodes, he’s very conscious of that, and he’s trying to give people as many ways in to classical music as possible. Okay. You don’t like classical music. Fine. We’re here to try to change that. Do you like Tuscany? Great. Then you’re going to love this episode. Hey, do you like fine cuisine? Oh, you do? Great. You’re going to love that. Do you love architecture, great architecture? Hey, this episode is for you. So I think points of entry is the keyword. It’s the key behind the philosophy of the show.

Jo Reed: I found the Haydn just fascinating, and it was like a violin extravaganza, because along with you, there was Geoff Nuttall, whose skill was matched completely by his enthusiasm. Can you tell us a little bit about him and how he came into that particular episode?

Scott Yoo: Geoff is an old friend. He is absolutely a wonderful violinist, a wonderful quartet leader, which is a different skill. And he absolutely is the person you want to talk to if you want somebody to be excited and passionate about Haydn. It was infectious. I’ve played maybe five or six of the string quartets of Haydn. I don’t know all of them. I’ve actually played more Mozart and Beethoven Quartets. But after filming that episode, I thought, “Oh, I got to get back into Haydn Quartets, because they’re so great.”

Jo Reed: Well, it’s interesting, because after listening, watching that episode, I thought, “Man, I have to get some Haydn Quartets.”

(Music Up)

Scott Yoo: He’s such an inventor. He has so many tricks up his sleeve. Every one is a little different, and he writes within a certain framework, but each one is completely different from the last. I visited Lucerne in the year 2000, and they had a whole bunch of frogs that were each painted by a different artist. Each frog was the same plastic shell, but each one was so different from the last, and I thought it was just fascinating, and I was hunting, “Hey, where’s another frog. I got to check out another frog.” And Haydn’s Quartets are like that. Within one framework, he’s able to make millions of different permutations, and it’s so rewarding.

Jo Reed: Well, you make wonderful connections in that between folk music and gypsy music and Haydn’s music. And I really liked how, you know, we tend to think of things as being in silos. And if there’s one thing that’s true about culture and music is that, oh, no, there are no silos.

Scott Yoo: Sure. I mean, for me, one of the really satisfying and-- for me, one of the really gratifying things about making this show is that I’m constantly learning myself. I did not know before making this show that 90 percent of Antonio Vivaldi’s manuscripts were lost until the 1940s. I just did not know that, because, as a music student, they were all available to me. But I was born after 1940, and I did not know the extent to which Haydn really lived in a cultural melting pot, sort of on the border of what we call Austria now and Hungary with sort of Viennese influence and gypsy influence. It’s really fascinating, and even some bagpipe in there. It’s really fascinating, and it’s fun to actually get to travel to where these composers actually lived, go to where they died, go to where they lived, where they were born. It’s really a privilege to get to be a part of something like that.

Jo Reed: Gabor Hamaki made my jaw drop with his virtuosity.

Scott Yoo: Oh, he’s incredible. He’s incredible.

Jo Reed: And I love gypsy music too, so, I mean, he was, for me, just like perfect combination. But what was so interesting was listening to the three of you talk about this music and the feelings of actually playing it. And I’m not a musician, but I often wonder, you know, especially-- well, not especially, but we’re talking about strings, so with a violin, you’re cradling it so close to you and those vibrations have to be going through you.

Scott Yoo: Oh, yeah. It’s funny. When you play the violin with headphones on, and so somehow your hearing is slightly altered, because you can still-- let me start that answer again.

Jo Reed: Sure.

Scott Yoo: Let me phrase that differently. It’s funny. When you play the violin and let’s say you have a cold and you can’t hear that well out of one ear or something, you can still kind of pull it off, because some of the hearing is actually coming from the vibrations through your body. I think that wind players have that as well, because their airstream is vibrating the instrument, and so they’re kind of getting the vibrations through their mouths. But certainly for a violin player, violist, you really feel connected to the vibrations, and it’s-- I don’t know. It’s why I want everybody to play the violin in America, because I feel that it’s really a lot of fun. I mean, it’s a hard instrument to play, but it’s really fun. It’s kind of a strange thing, to have this little wooden box vibrate so wildly just using your two hands. No electricity needed.

Jo Reed: Right. Exactly. Well, you played in a quartet with Gabor and with Geoff. I think it was in Hungary, this beautiful room, and I would love you to describe the room. But then, does it feel different somehow to be playing in a room that itself is a work of art?

Scott Yoo: Okay. So that’s a very good question. That’s a loaded question. I’ll try to answer it as best as I can. So that was in, I believe, Eisenstadt, which is now part of Austria.

Jo Reed: Yes.

Scott Yoo: It’s called Esterhazy Palace, and the actual room that we were playing that scene in, if I’m getting you correctly, that’s called the Haydnsaal, or the Haydn Hall. And it sounds as good as it looks. It was-- I saw the Haydn episode with a bunch of people socially distanced on somebody’s backyard. Let me say that again. I watched that episode in somebody’s backyard socially distanced. They bought a big screen so they could project the episode onto a screen. And when they showed the ceiling of the Haydnsaal, everybody went, “Oh” and everybody gasped. And it actually was better in person than it was on TV. It’s really a striking place. And what’s amazing about that place is the acoustic. I mean, your violin, it feels like it lights up. You know, they have those sneakers that light up for children. When you step, they make a little light. Like your violin was lighting up in the Haydnsaal. It was amazing. It’s kind of like a good mirror. Like you look at yourself and you suddenly look more handsome, more pretty, whatever just because of that mirror. That’s what that Haydnsaal did. And there’s actually a digital reverberation company. So it adds artificial reverberation to your concert tape or your music, whatever. They actually can synthetically create the reverberation from the Haydnsaal. So that’s how famous that room is.

Jo Reed: Wow. Wow. How much do you guys rehearse beforehand? I mean, I’m sure every musician comes prepared, but there’s a lot of music that’s played in each episode, and I wonder how that comes together.

Scott Yoo: Well, that really depends. Some scenes like the Vivaldi where I’m playing the “L’Amoroso Concerto” in the Turin Library, that was just pure sight reading, because I was literally reading that. Other places like say the Haydn Quartet that the St. Lawrence Quartet played, they’d probably been rehearsing that for a while, because they were getting ready for a concert. So it really all depends. Harry, the director, really likes for these scenes to feel spontaneous. And sometimes in order for them to feel spontaneous, he makes sure that they are spontaneous. So literally, he’ll just sort of throw something at us and say, “Do this.” And if it’s not good, it won’t make it into the show. But if it’s good, then it feels very spontaneous.

Jo Reed: I was very moved by the program on Franz Schubert. And, again, you had a very specific approach to him. It was very different from the Haydn or the Vivaldi or the Mozart. Explain this approach to the music of Schubert.

Scott Yoo: Well, Harry had a really beautiful idea for the Schubert episode. Schubert died so young. He never celebrated his 32nd birthday, and Harry proposed the idea of why not show Schubert’s character through other young musicians who were Schubert’s age and have a 26-year-old play the music of a 26-year-old Schubert. It was very moving to me, because I guess, first of all, more than any other composer-- because first of all, more than any other episode, what hung over us was that Schubert died young. That was the main thesis of the entire episode. And to see these people play, these brilliant young musicians play-- what just kept hitting me over the head over and over was that Haydn-- what kept hitting me over the head was that Schubert was a kid. He was a kid, and he wrote all of this fantastic music that has withstood hundreds of years of scrutiny, and he’s still great, and he still died when he was 31 years old. It’s mindboggling to me.

Jo Reed: And also the amount of music that he wrote. What did you say, 600 lieders, I mean, aside from sonatas and symphonies and quintets, blah, blah, blah.

Scott Yoo: It’s absurd. It’s absurd. I mean, and it’s the volume, 600. So many of them are masterpieces. It’s the heights. I mean, something like the “Cello Quintet” that he wrote in the last few months of his life that-- most classical musicians you speak to will say that’s the greatest piece of chamber music ever written, and he wrote it when he was-- he wasn’t 62. He was 31. And to me-- I mean, to have the wisdom to write a piece like that, you’ve got to be several hundred years old. This guy was just 31. Incredible.

Jo Reed: And it was also so moving, because it’s not as though he was celebrated during his life. He wasn’t. He was impoverished, and he died because he was sick. It’s not like he got thrown by a horse and hit his head. I mean, he had a life of really profound suffering.

Scott Yoo: Yes. Yes. Absolutely. I mean, there are famous stories of Schubert living the ultimate Bohemian life and not in a good way, sleeping on people’s couches and trying to figure out how he’s going to scrape together money for this or scrape together money for that. He did experience a little bit of success in his last year, and then he died. That’s why we picked the young artists that we did, because these are some of the most brilliant players there are and singers there are. But, you know, some of them are still struggling, because they’re young. It’s very poignant. My father used to play some of those Schubert songs on the piano. He wasn’t really a pianist, but he could sort of noodle around a little bit. So I kind of grew up with that music even as a child.

Jo Reed: I was going to ask you, actually, because you started playing the violin when you were three. So I assume your parents were musicians. Am I wrong in thinking that?

Scott Yoo: They were not musicians. My father had a huge record collection, and he had a very discerning ear. My father immigrated from Korea when he was young to study at Davidson College, which is a small liberal arts school in the south, and he had a huge record collection of Heifetz, Milstein, Serkin, Horowitz, all the greats, Toscanini, Zell. My mother grew up in Japan, in Tokyo. And when she was a high schooler, she heard the famous Japanese violinist, Masuko Ushioda, play a recital at her school, and she said that if she had a child, she would have them play that instrument, and that instrument happened to be the violin. So it’s clear that these concerts that are done at schools are actually pretty important. So both of them loved music, but both of them were not musicians.

Jo Reed: When did you actually come to love the violin?

Scott Yoo: That’s a really good question. When I was eight years old, I started performing the Mozart 5th Violin Concerto, and once you get to play music that the pros play and you’re not playing “Go Tell Aunt Rhody,” I think that’s when the instrument gets to be a lot of fun.

Jo Reed: Well, you also played Mendelssohn with the Boston Symphony when you were, what, 12 years old?

Scott Yoo: Something like that, yeah. It was a long time ago, but I still remember it.

Jo Reed: I wonder what you remember. Yeah. What do you remember of that experience, other than I assume feeling small?

Scott Yoo: Well, several things. One was that I remember that Henryk Szeryng-- several things. One thing I remember was that-- so those concerts were on a Saturday, and Henryk Szeryng was the soloist with the Boston Symphony for their normal concerts, and so I passed by his dressing room, and it said, “Henryk Szeryng” on it. And, of course, Henryk Szeryng was an idol of mine. So to get to walk by his dressing room, I remember thinking that was such a huge honor. I remember the orchestra played so perfectly it sounded like the recording, except that-- it’s kind of like singing karaoke except that you’re not singing with a CD. You’re actually singing with a band. That’s kind of what it felt like. It was ridiculously exciting, and I don’t know. I will always treasure that memory, and that’s-- also that hall that the Boston Symphony performs in, Symphony Hall is one of the, you know, I don’t know, two or three greatest concert venues that mankind has known. It’s just so incredible. So just to get to make a sound in that room is just such an honor.

Jo Reed: But yet, when you went to Harvard, you studied physics. So I’m curious about the switch here.

Scott Yoo: Well, that is a little bit of a longer story. What happened was: in high school, I had gotten into Harvard, and my best friend at the time had gotten into the University of Pennsylvania, and we had a sleepover to celebrate. And for some reason, we were just sleeping on the floor at a friend’s house, and my friend accidentally stepped on my index finger and broke it. And so I couldn’t play the violin with four fingers in my left hand. I lost the index finger. That’s what you call the first finger in violin lingo, so I was using the second, third, and fourth fingers for several months. And by the time I would heal, it would probably be May. And by that time, the question is are my fingers going to work properly or not. And so I decided that the safest thing to do would be to go to Harvard and study something else. And if the violin career worked out, great. And if it didn’t work out, then I would have other options. Fortunately, my hand healed. It actually didn’t heal completely. There’s still a screw in the joint, and it’s not as strong as it used to be. My first finger used to be the strongest one, and it’s a little weaker than it used to be. But, of course, going to Harvard, I just learned so much from my colleagues and friends and had so many interesting experiences, and it changed my musical career forever.

Jo Reed: Well, is that were you began conducting?

Scott Yoo: It is. My college orchestra’s conductor called me one morning and said, “I’m sick. You conduct the rehearsal.” And the rehearsal was Mozart’s 35th Symphony and “The Right of Spring.” And so I spent the entire day getting ready for that rehearsal and realizing, “Wow, if I could spend every day doing what I’m doing now, that would be a really happy life.” And I think that was when I first started thinking maybe I should switch over to become a conductor. And then one of my good friends in school, he and I ended up organizing a benefit concert of Vivaldi’s “Four Seasons,” and we were very successful. We sold out the hall, and we raised a lot of money for what we were raising money for. And we decided, “Wow, we should keep doing this,” so we started a chamber orchestra we called Metamorphosen, which is what I did all in my 20 and that led to all of the other opportunities that I had in my career. And, actually, I met my wife through the orchestra, so that was very nice.

Jo Reed: This is what I’m curious about. I’m curious about what you get from playing the violin as opposed to what you get from conducting, because I’m assuming they both feed you, but perhaps feed different parts of you.

Scott Yoo: That’s a really excellent question, Jo. The thing about the violin is that you can do anything you want. It’s like riding a children’s bike. You can draw lines in the pavement. You can make sharp turns. It’s so immediate, because you’re controlling the sound. What wonderful about conducting is that you’re driving not a children’s bicycle. You’re driving a tanker. You don’t have as much control. You can’t swerve around a pebble like you can with a children’s bike, but you’re just driving something a lot bigger. One thing that I love about conducting that I really do not like about violin; with conducting, if you learn something and you learn it properly, it’s there. With violin playing, if you learn something and you practice it and practice it and practice it, it may fail you in the concert. It’s very similar to figure skaters when they-- they can do a triple axel no problem in practice. But then in the short program of the Olympics, then suddenly their triple axel goes out for no reason. And violin has a little bit of that acrobatic element that is very frustrating, because no matter how well prepared you are, something may go.

Jo Reed: You know, obviously, the pandemic has put a full stop to public performances and traveling. You mentioned that Beethoven got caught in the crossfires of the pandemic. Was everything else in the can?

Scott Yoo: We shot Mozart entirely during the pandemic. So every scene that you see us-- so every scene that you see us, we are socially distancing even though it doesn’t look like it. The orchestra that we shot, every single person was socially distanced. When we were shooting Steven Copes, the Concert Master of The Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra, he didn’t have a mask on, but everybody else in the orchestra did. When we were shooting the bassists, the cellos had their masks on and the violas had their masks on. When we had the violists on camera, the violins had their masks on. And so it was this really elaborate dance to keep everyone masked for as long as humanly possible.

Jo Reed: Now, can you tell me about playing when you’re socially distant with masks? Is listening different, visual cues different?

Scott Yoo: It’s so hard. It’s so hard. First of all, we forget how much the mouth is important when you’re cueing. People look at other people’s mouths, and now you can’t see anybody’s mouths, and that’s tough. The second problem is that you can’t hear each other. So you really have to go on physical cues, but those are diminished. And the last thing that’s so, so, so hard is that there’s a little bit of a delay. So apparently, for every foot apart, there’s a one millisecond delay, which seems like it’s not so much, but it really does add up when you have that many players and everybody is that far apart. And so it’s kind of like when your computer is maybe old and you type the letter J-o for Jo. And by the time you’re typing in Reed, the J and the O have just appeared, like it’s slow. That’s what playing in social distanced circumstances feels like. It’s just very uncomfortable.

Jo Reed: Have you played in any virtual performances?

Scott Yoo: I have. At another festival that I participate in, it’s called the Colorado College Music Festival. It’s very June, we did a socially distanced concert at our regular hall, but with no audience. And our audience was a camera that was live streaming to Facebook Live. And, you know, that was a strange experience too, not so much fun, but at least we had something going on. It’s nice to make music.

Jo Reed: Well, in terms of classical music performance, Scott, do you have a sense of what the short-term/long-term impact of the pandemic might be? And I’m thinking about smaller and even mid-size companies, or those serving underserved communities.

Scott Yoo: Jo, those are the ones I’m most worried about. I’m sure that the Cleveland Orchestra is going to be fine. I’m sure that the New York Phil Harmonic will be fine. Hold on a second. Guys, I’m just finishing up another interview, but I wanted to get on so that you knew I was here. I’m sure that the New York Phil Harmonic will be fine. I’m sure that the Metropolitan Museum of Art will be fine, but it’s that symphony say in Sioux Falls or in Quad Cities, or in Lincoln, Nebraska. I’m worried more about those places. Hopefully, the country will rally together and really sort of help out the little guy, because that’s very, very-- we’re in precarious times for the performing arts, for sure, and for art in general.

Jo Reed: And I’m also thinking about contemporary work, because you are a champion of it and conducted often, and I can see how it might be really rough going for contemporary composers to get their work out.

Scott Yoo: Especially now, because companies and orchestras, they’re having-- I’m going to put money that everybody’s going to pull back and not do anything too “out there” in order to just get their audience to come back, which that is the smart play. But, of course, the people who get left behind are the people who are doing contemporary works.

Jo Reed: Do you think we’ll be seeing contemporary composers featured on “Now Hear This?” Do you see it sort of--

Scott Yoo: Absolutely. Absolutely. Absolutely.

Jo Reed: Let’s end with this. Is there a piece of music that you played that perhaps you hadn’t played before that you are just so happy is now a part of your life?

Scott Yoo: Oh, that’s an easy question to answer. For me, I’m really grateful to get to play that Haydn Quartet that I played the first violin in part, second violin part, viola part and cello part at the beginning of the Haydn episode. I’d never played that quartet before. But I must say, Jo, it’s been running through my head for the last two weeks sort of as the soundtrack to my life. There’s so much going on and there’s so much energy and friction and levity. I don’t know. I love it.

Jo Reed: And you played all four parts.

Scott Yoo: Well, I played the cello part and the viola, but pretty close.

Jo Reed: Yeah. That was great. Scott, thank you for giving me your time. I know you have another call waiting, but I really appreciate. And I’m really not joking. This has not been a good week, and last night was a gift. Thank you.

Scott Yoo: Thank you, Jo. It’s an honor to speak with you.

Jo Reed: That was violinist and conductor Scott Yoo—He’s the host of Now Hear This presented by Great Performances. Look for the series on your local PBS station or on Passport.

You’ve been listening to Art Works produced at the National Endowment for the Arts. Subscribe to Art Works and leave us a rating on Apple—it helps people to find us. For the National Endowment for the Arts, I’m Josephine Reed. Stay safe and thanks for listening.

Scott Yoo is a wonderful guide to the music and the influences of some of the great composers of western classical music. Now Hear Thisis in its second season—it’s a four-part mini-series from Great Performances. Yoo describes it as influenced by Anthony Bourdain but “substitute music for food.” But it is a feast for the ears and for the eyes. Yoo travels to the places where composers like Vivaldi, Haydn, and Schubert lived and worked; digs into the cultures that shaped them, the food they ate, the music they heard, and of course, the glorious music that they created. In a Covid-altered universe where performing art and traveling is out of reach, Now Hear This is a series that goes far in filling the breach for the classical music lover, the frustrated traveler, and the curious-minded.